Engineering teams can often improve their long-term development velocity by slowing down in the short term.

A shared misunderstanding 🔗

Technical debt is an often debated topic. Like most concepts in software, it isn’t particularly difficult to find arguments supporting opposite sides of the spectrum - in a single minute of searching I was able to find that some believe that technical debt doesn’t exist, while others feel that technical debt is the most important aspect of product development. From the conversations that I’ve had with others in the industry, both within my place of work and with technical leaders from other companies, I’ve come to believe that one of the root causes of the gap between these viewpoints is primarily definitional.

Part of the reason that some people don’t like the term “technical debt” is that they feel it becomes an excuse. To these individuals, everything that software engineers don’t like within the system on which they’re working gets labeled as debt, and that debt becomes a boogeyman that gets blamed for all of their problems. Those on the other side of the argument feel almost the exact opposite: technical debt gets little attention and they’re forced to spend inordinate amounts of time struggling against implementations and concepts that make it more difficult to make changes than it otherwise could be. An interesting realization (and something that makes this conversation particularly difficult) is that both groups can be right at the same time. This can be true only because the two groups are misunderstanding one another. But where does this misunderstanding come from?

The phrase “technical debt” was originally coined by Ward Cunningham, one of the co-authors of the Agile Manifesto. He since explained what he meant when he originated the term. Two excerpts from his explanation are particularly important to the ideas that I want to discuss:

With borrowed money you can do something sooner than you might otherwise, but then until you pay back that money you’ll be paying interest. I thought borrowing money was a good idea, I thought that rushing software out the door to get some experience with it was a good idea, but that of course, you would eventually go back and as you learned things about that software you would repay that loan by refactoring the program to reflect your experience as you acquired it.

You know, if you want to be able to go into debt that way by developing software that you don’t completely understand, you are wise to make that software reflect your understanding as best as you can, so that when it does come time to refactor, it’s clear what you were thinking when you wrote it, making it easier to refactor it into what your current thinking is now. In other words, the whole debt metaphor, let’s say, the ability to pay back debt, and make the debt metaphor work for your advantage depends upon your writing code that is clean enough to be able to refactor as you come to understand your problem.

From Ward’s explanation, we learn that technical debt doesn’t mean “poorly written code” or “implementation in the system that annoys developers”; rather, it implies a choice that was made in the past. There is never any excuse for writing “bad” code, but there is a time and a place to make sub-optimal decisions during product development in order to shorten time to initial delivery. The longer those sub-optimal decisions are allowed to persist within the system, the larger their negative impact.

The misunderstanding between the two camps is caused at least in part by the fact that debt is so often associated with anything that an engineering team perceives to slow them down. I believe this situation is inevitable with any post-hoc debt classification strategy, and therefore should be avoided in lieu of more effective options.

Technical debt should be intentional 🔗

I believe that technical debt is most useful as a concept when it’s thought of as something that’s taken on knowingly. If we think about taking the debt metaphor literally, this is also the definition that seems to make the most sense considering that financial debt isn’t something that can happen to someone without their knowledge. When we take on financial debt, we’re accepting a greater total payment over time in order to buy something that we wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford in the present. Just so with technical debt, except now the concern is with development time rather than money: we’re accepting a greater amount of total development time over the lifetime of the product in exchange for a faster initial delivery.

One of the great things about attaching a requirement of knowledge to technical debt is that it automatically solves problems on both side of the misunderstanding presented earlier:

- It provides much better visibility into the amount of debt that’s been taken on in order to build a product, and how much of that debt hasn’t been paid down

- Debt can’t be overinflated or understated because it’s classified at the time that it’s taken on rather than retroactively

- The difference between routine maintenance and debt pay-down is clear; maintenance is work that must be done that is neither classified as debt nor as an enhancement/feature of the product

- Because debt is explicitly classified, it can be prioritized against other types of work intentionally

It also allows teams, product managers, and stakeholders to have more informed and well-reasoned discussions about their product throughout the development process. Developers and team leads should be able to clearly communicate when debt is being taken on in order to hit a deadline, product managers gain the ability to clearly see debt growing in the product’s backlog, and stakeholders can work with both groups to make well-reasoned decisions about when the team should push for new functionality and when it makes more sense to work on insufficient foundations.

It can be difficult for PMs and non-technical stakeholders to truly understand the long-term impact of technical debt, but I have seen this method work in practice by implementing it myself. I believe the most important key to unlocking these benefits is shared understanding. When working with the idea of debt in this way, it becomes very easy for developers to answer the question “What is technical debt?” and explain how these past decisions add up to make future development more difficult.

Of course, none of this comes for free. For such a system to work to its fullest, it has to be adopted very early in the product development process, ideally from the initial onset of the project. It requires building the shared understanding between developers and non-technical personnel of what debt means and why it’s important to pay attention to. It requires at least a baseline level of buy-in from an organization that overall system quality is important to the bottom line. None of these tasks are trivial, but neither are they difficult, and I believe the effort is well worth the payoff.

Real world example 🔗

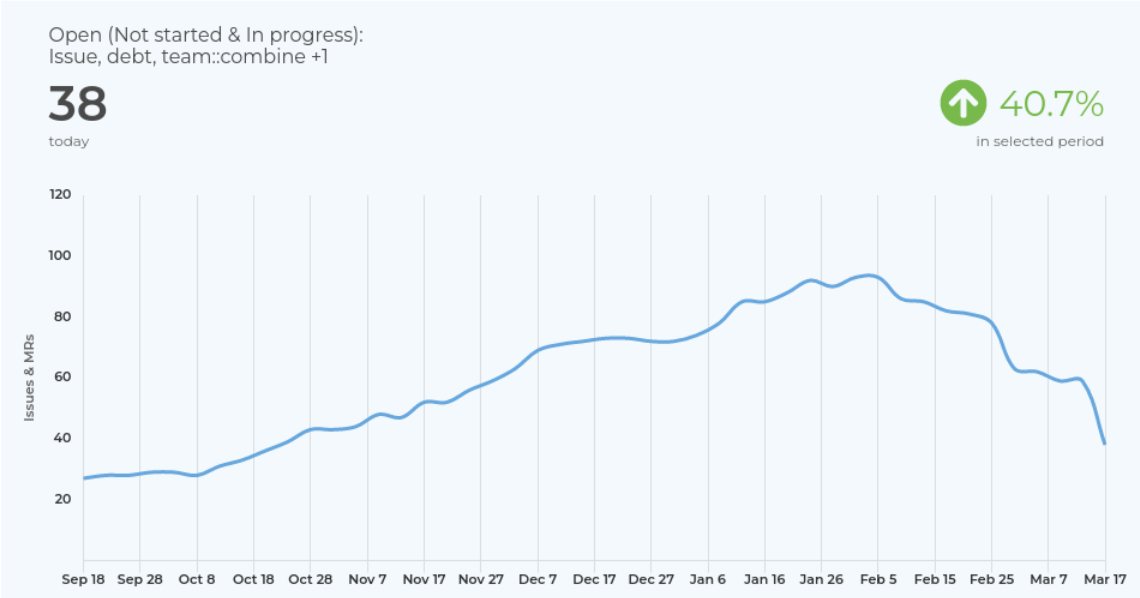

As a more concrete demonstration of what these ideas look like, I’ve pulled some high-level data from one of my teams' most recent deliveries. Here is that team’s 6-month debt trend:

Q4 was a “push” quarter for this team - they were working hard to hit a very specific deadline. During this time, they made the decision that accruing a significant amount of debt was the only way that they were going to be able to make it happen. After the team successfully hit the deadline, they were then able to revert to a more sustainable mode of development; throughout Q1, they paid down a large portion of the debt that they had built up during the push.

Crucially, we were able to use the data available from this methodology as an aid to explain the importance of this work to stakeholders and help them understand why short-term velocity on further functionality for the system would be reduced while a portion of development time was spent paying down this debt.

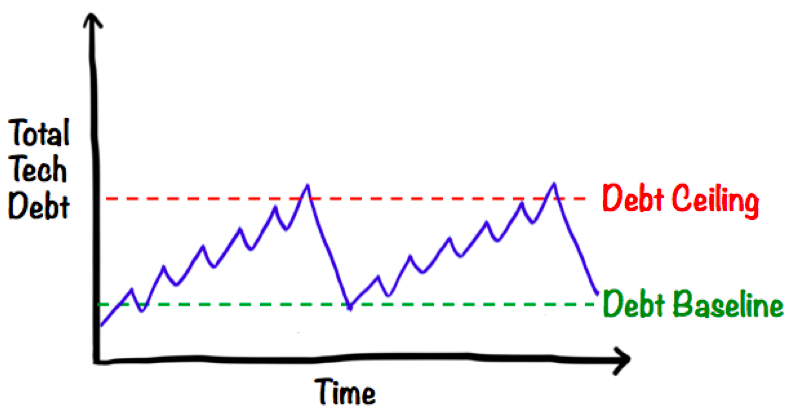

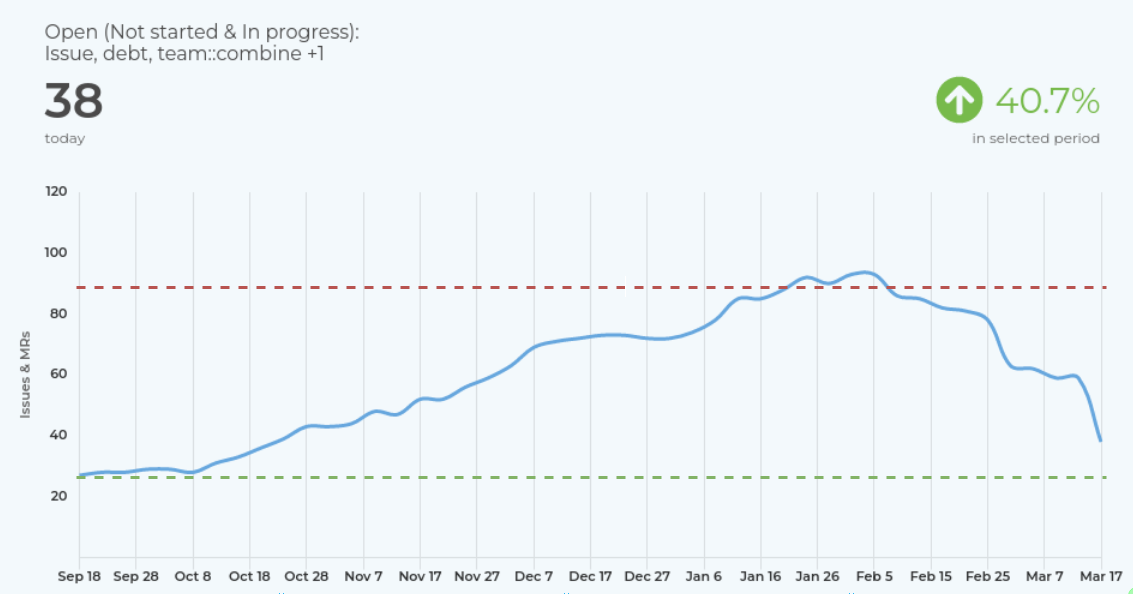

I found it interesting to compare this trend to the ideal debt charts put forth in yet another blog post about technical debt. Here’s an idealized chart compared to the team’s debt baseline and ceiling:

We can see that the debt management may not be completely ideal, but the team has been able to successfully pay their debt down throughout the course of a quarter and are once again much closer to their debt baseline than they are to their ceiling.

Slow is smooth, smooth is fast 🔗

Following these ideas, one of the mantras that I use with all of my development teams is “We have to go slow if we want to move fast”. It sounds a bit silly perhaps, but I like sayings that will stick with people and the idea is simple: slowing down gives us more time to think, more time to think leads to better designs, and better designs lend themselves to easier change in the future. There are many situations where incurring debt makes sense, but there are at least as many (and, I suspect, likely many more) where the best way to pay down debt is to never take it on at all. When we do need to incur debt, we should do so intentionally and with at least some level of understanding of when and how we plan to pay that debt down.

I particularly like this saying because it also has applications to many other areas of the development and leadership process outside of technical debt specifically. Let’s consider a contrived example, based on a true story:

A defect has been found in a production system that the team believes is being caused somehow due to the distributed nature of the system. Two engineers separately attempt to identify the root cause of the issue, but are unable to find the source of the problem after a week of investigation. A third engineer is brought in and is able to identify and resolve the issue within a few days.

The first thought a lead may have is to increase their reliance on that third engineer, always bringing them in to triage issues when they arise. The idea seems reasonable; after all, that engineer has proven that they can be much more effective when it comes to issue resolution than the others. If, however, we take a longer-term view of the situation, I believe this wouldn’t be the best solution for at least two reasons:

- We’ve introduced a single point of failure. If that engineer leaves the team or the company, we’ll be right back to struggling with issues

- We’re assuming that identifying and resolving these issues is the most valuable thing that the third engineer could be doing. It’s very possible that the opportunity cost of assigning them to triage is higher than the cost of the defect

With these failure modes in mind, it may make more sense to ask the third engineer to train the other engineers on their issue resolution methodology. Future issues should be resolved by other engineers before enlisting the help of the third, bringing them in only when the rest of the team is stumped (or perhaps has reached a predefined time-box).

While the latter is very likely to lead to longer issue resolution times in the short term, these times are also likely to decrease as the other engineers gain familiarity and proficiency with the issue resolution process. Once we’ve reached that point, we now have three engineers capable of this type of issue resolution instead of only one. We made the intentional decision to allow progress to be slower in the short term in order to effectively triple our longer term velocity/capacity for this type of work.

Conclusion 🔗

There’s isn’t a universal answer to the best way to balance development velocity against technical debt. Thinking of debt as something taken on intentionally by a team to increase their short-term velocity at the expense of future work is an easy to apply strategy that has many benefits to engineering teams while also simplifying the concept for less technical individuals. By measuring accrued debt against long-term baselines and ceilings, engineering managers can get a feel for how much this debt is impacting their teams, and this data can be used to aid in prioritization decisions and high-level discussions with stakeholders.

If your goal to to increase your teams’ overall development velocity in the long term, remember that you may want to slow down so that you can move fast.