Incremental progress on large projects can be achieved by developing functional stripes across the system's components

When planning the delivery of a software project, there are many different strategies for handling the design and implementation of the system. At the extremes, we could attempt to complete a fully-specified design before writing any code at all, or we could start writing code without putting any thought towards our design and architecture at all. Most engineers would prefer not to live at either of these extremes, so how can we do better?

System design is a fundamentally complex and difficult task, at least in part because our knowledge and experience is finite. Unless we have a significant amount of experience building a very similar system, it’s likely that at least some portion of our prior experience won’t translate directly to the results that we expect when applied to the new system. In general, we’re unlikely to be able to generate a completely correct or optimal system design without investing an extreme amount of time and effort up front.

With this in mind, we should normally prefer a highly iterative design and implementation strategy. There are many benefits to iterative processes in software development: they allow us to incrementally modify our designs with new knowledge and experience that we’ve gained from the existing implementation, provide a sense of impact and motivation with each release, and allow us to deploy more frequently to learn and collect feedback from users.

One such strategy that I have found enjoyable and effective for both personal and professional projects I like to call striped development. I was motivated to write this post after reading an article about writing a compiler that begins by describing the author’s implementation strategy, which is very similar to the striped development concept that I’ve been using for many years now.

Definition 🔗

Software systems can be thought of as a set of components that interact with each other to provide some externally visible functionality. Each system-level component can itself be composed of other components; while these inner components will usually not be externally visible, these properties of composition and encapsulation is integral to how we often think about designing and implementing software. The C4 model, for example, attempts to formalize these ideas into a diagramming and documentation framework (quite successfully, in my opinion).

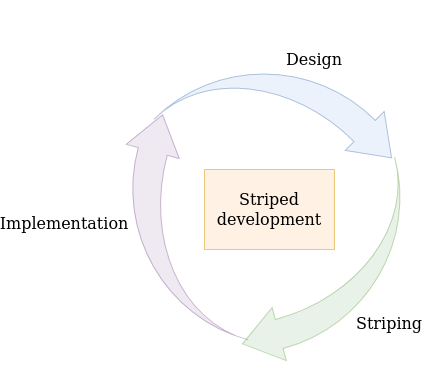

Striped development is an iterative approach to organizing work that embraces this fractal approach to system design and implementation by way of three repeating phases:

- Design: generate a high-level design for the components that comprise the system

- Striping: decide upon functionally-complete stripes that cut across those components

- Implementation: implement each stripe in turn, returning to the first step after each stripe to update the design and striping with any new information gained from the implementation

The most important part of this strategy is the circular nature of the phases. When we complete an implementation phase, we’re not done; rather, this simply means that it’s time for us to return to the design phase where we can continue to improve upon the structure of the system as a whole:

Before the end of the post I’ll go through a complete example of how this looks in practice, but it’s first useful to understand each of the individual phases in slightly more depth.

Design 🔗

System design in general is a deep topic, certainly much too deep to be reasonably explained in a short post such as this. We can approach the design phase in many ways, but when working with striped development, I often like to think of it as a three-step process:

- Decide which components our system requires

- Define the dependencies between those components

- Optionally, specify the API boundary (data structures and operations) for each dependency

- This third step generally becomes more useful further into the project when the system components and concepts have begun to stabilize

At first glance, the design phase may sound a bit like some classic advice:

If we already know how to generate a high-level design for the components that comprise the system and how they interact, why do we need this development methodology at all? Can’t we just take our design, implement it, and move on?

The key insight is that the design we generate when we first start the development process is likely to look quite different from the design when we’re finished. We could try to fight this idea with more planning, more information gathering, or more in-depth requirement specification, but in practice it’s usually much easier (and more effective) to embrace it. At each pass through the striped development process, rather than trying to create a fully specified, completely correct, or perfectly optimized design, we are somewhat freed by the knowledge that we’ll be returning to the design phase upon completion of each implementation phase.

Thus, the initial design phase is really about giving ourselves a reasonable starting point. Subsequent design phases improve upon the existing design, ultimately converging upon an overall system structure that makes it easy to quickly modify system behavior. This is another benefit of the striping methodology: by repeatedly modifying stripes through the entire system architecture, we quickly learn of deficiencies in our existing design. Whenever we run into trouble modifying one of our sub-components or find it difficult to implement a new concept into the system, we’ve identified an area that we can improve the way that our system is structured.

Striping 🔗

Striping is the determination of functional cross-sections that can be implemented across the current iteration of the system design. Choosing stripes can often be the most difficult part of applying striped development; often, it’s not readily apparent how we can structure our changes so that they cut through the entire system end-to-end. Further, we should attempt to select stripes that will teach us as much as possible about our design and how the system’s components work together. This usually means selecting stripes in groups that build upon each other in some way. If we choose three stripes that are almost entirely orthogonal in their functionality, it’s possible that we could implement all three without identifying a critical oversight in the design of our component interactions.

When striping, there’s a balance to be struck: selecting more stripes up front will give you a better idea of what the overall development process will look like, but also makes it more likely that some of the stripes may have to be changed (or removed entirely) as the structure of the system evolves. In my experience, somewhere between three and five stripes tends to be a good balance, but ultimately this will depend on the perceived certainty/stability of the design and your ability to effectively implement it.

Implementation 🔗

Implementation is the fun part! Here, we begin work on the next selected stripe and implement it to completion. Usually, I prefer for stripe implementation to include all aspects of “production quality” code, including:

- Tests

- Documentation

- Resolution of all warnings and linting violations

- Etc.

While it’s true that some of this effort is likely to be wasted (as not all implemented code will make it to our final version due to how quickly we’ll be iterating), working with complete implementations from the beginning of the development process makes it much easier to understand how working with the system is going to feel once it’s complete. If we try to blast through implementation phases as quickly as possible without cleaning up after ourselves, we may reach a point where we find that implementing reasonable tests is very difficult or that our system is hard to explain with written documentation. These are clear signs that complexity has not been properly managed.

In the short term, it may feel like doing all of this is slowing you down. If we’re talking about amount accomplished in a few days, this is most likely true; however, as I’ve be addressed in Go Slow to Move Fast, over a longer period of time, keeping up with these basic maintenance and quality activities will probably increase your total velocity over the same time period. It’s counter-intuitive, but give it a try and see if it holds true for you as it does for me.

As we’ve alluded to in earlier sections, completing the implementation phase fully has two primary benefits:

We frequently deploy functionally complete changes to our users 🔗

Deploying changes to users is useful for many reasons. First and foremost, it allows us to collect feedback from the users. This is vital to overall project success. As the authors and creators of a system, we see each feature and idiosyncrasy through a vastly different lens than anyone who wasn’t involved in the development process. We like to think that we can be impartial judges of our own work, but more often than not, this proves to be nearly impossible. Even if the system is not yet complete (as it won’t be for most of the development process), users can still provide us with valuable insight that we are completely blind to without the un-invested observer to point it out to us.

Secondarily, deploying often is also a great motivating factor for the developers of the project. Whether it’s a hobby project that you’re tackling on your own or a corporate initiative comprised of many development teams, releasing code to some version of “production” feels good and demonstrates tangible progress both to yourself and to anyone who’s interested in the project’s outcome. If you’ve ever spent weeks trying to design a system or library perfectly only to lose interest before even getting started, lack of tangible progress could be to blame. In some ways, this is almost a trick or a hack - it’s as useful for us to demonstrate progress to ourselves as it is to anyone else!

We learn about the efficacy of our existing design and implementation 🔗

By consistently adding functionality to the system by modify each component within it, we’re able to easily understand how well we have done with design fundamentals like encapsulation, decoupling, and separation of concerns. Difficulty implementing a stripe into the system is a signal that our design may be missing some crucial element, or possibly that our implementation has not done a good job of realizing the design.

Implementing tests as we complete each stripe allows us to ensure that the important properties of each component remain testable as we’re making continued changes within the system.

Writing documentation for public interfaces and system-level concepts forces us to be able to explain why we’ve made the decisions that we have and how they fit together to provide the functionality that we’re aiming for.

Paying attention to the linter and compiler warnings ensures that we’re not relying upon shaky foundations for any of the core components or libraries that comprise the foundation of our system.

Really, this is all basic software engineering stuff, but holding ourselves to it for every stripe that we implement provides some structure to the way that we work: we don’t necessarily have to write documentation or clean up a compiler warning immediately when we write a new public API, but we do require ourselves to do it before we will consider our current stripe complete. This makes each stripe act like a sort of checkpoint that guides us to follow the best practices that we know are important, but that can also easily fall by the wayside as we get swept up in the flow of implementation.

Example 🔗

So, I talked a lot about what striped development is and how it can benefit us, but what does this process really look like?

As referenced earlier in the post, I was originally inspired to write this post by another author’s explanation of the implementation strategy they used to implement a compiler. Recently, I have been working on a compiler of my own using the striped development methodology. The language is called Jackal. This is a very young project (I’ve completed only one pass through the development loop), but the structure of a compiler is very well-suited to this style of development, so a discussion of Jackal’s initial development is a real-world way to showcase how striped development works in practice.

Design 🔗

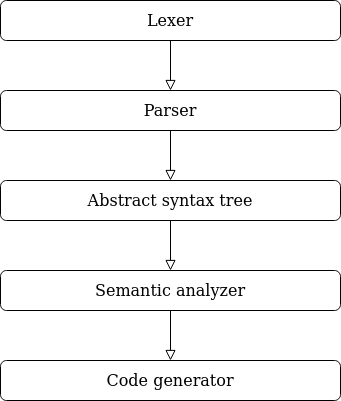

First, we have to come up with an initial design that we can work off of. For a compiler, this is mostly done for us as we can leverage the vast amount of literature and public works available to understand a good starting point. My first stripe design ended up extremely simple:

You can probably tell that I’m not a compiler design expert, but I do know that I’ll need a way to lex and parse the source code, transform it into an intermediate representation, type-check the IR, and finally generate machine code. Critically, this design is missing at least one component that will be a strict requirement before the compiler can be called complete: an optimizer. While we’re likely missing more than just this one component in reality, this showcases the idea that our design need not be complete during any individual phase of striped development. I know that I’ll need an optimizer in the future, but I don’t yet have the context or knowledge to reasonably implement this component into my stripes, so I’ve purposefully delayed those decisions to a future phase.

It’s also worth highlighting that this initial design is very high level. It specifies only the least-granular components within the system, providing no detail yet as to how each of these components might be implemented or what the APIs between them should look like. This early lack of detail is another hallmark of the striped development methodology. As we begin to implement and learn more about how our system works, we will continuously update this design to add more detail as decisions begin to solidify. Creating a design diagram just to change it every week is probably not particularly useful, but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t create any diagram at all: regardless of what specific decisions I make within each of these 5 components, it’s highly unlikely that any of them will go away entirely, and the data flow between them is likely to remain stable as well.

As development of the system continues, this diagram will evolve and expand to contain more granular detail. It can be thought of as a sort of evolving map, both documenting where we are currently and where we aim to go in the future.

Striping 🔗

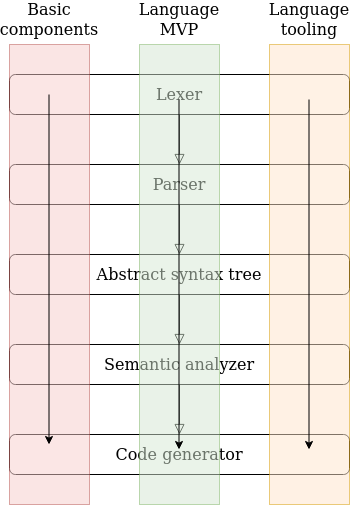

With our initial design complete, we can now move on to the second phase: selecting our stripes. I expect this project to be even more iterative than usual due to my inexperience with language design and my desire to experiment with different ideas, so I decided to keep the forecasting to a minimum and define only three stripes to start:

- Use a tiny language definition to implement all 5 components and see them work together end-to-end

- Replace the tiny language definition with an MVP for how I expect Jackal to look

- Implement integrated language tooling for the MVP

It’s important to highlight that I decided on these stripes before starting any development. These stripes now comprise a plan for how I’m going to implement the system and what sort of considerations I should be taking into account during each of the implementation phases. While working on each stripe, I’ll have a very specific goal to complete, but I’ll also have a picture of where I’ll be going in the future. Since the cycle returns us to the striping phase after each implementation phase is complete, we should always have our next three stripes selected so that we have a good idea of what’s to come.

We can visualize stripes as a sort of overlay atop our design from the previous phase:

Let’s briefly consider how these stripes relate to one another and how they help us achieve our greater goal: a full programming language working from source code to running executable.

First stripe 🔗

The first stripe exists to give us a strong base of code to work within. The language I chose to use as a model for implementing each component had nothing to do with the actual Jackal language that will eventually be implemented using these components, but was simple enough that it allowed me to focus instead on the overall structure and functionality within each component. I was able to explore different decisions around how those components might interact with one another and how they should interact with the outside world (an application of Imperative Shell, Functional Core, which I plan to post about in the future).

Second stripe 🔗

The second stripe exists for two reasons:

- It provides us with a working version of the language that we can begin to experiment with

- It tests our implementation of the design: how difficult will it be to swap the underlying language out from our components?

The first is more important from a delivery perspective, while the second is more important from a development perspective. Regardless of which we care more about, this single phase allows us to understand both simultaneously.

This also demonstrates the “frequent deployment” concept that we touched on in the striping definition: getting an initial MVP version of the language working will be a huge motivating factor in the language’s continued development by making it a real working system that I can iterate on instead of a theoretical idea that I’m thinking about.

Third stripe 🔗

Finally, the third stripe may seem somewhat out of place, but I’ve selected it primarily due to my goals for the language and because I know that having integrated tooling this early in the development process will make writing Jackal code feel much more “real” than it would without this type of functionality.

One of Jackal’s primary goals is to make as much tooling as possible first-class and vended with the compiler itself. The ultimate success would be that no language-specific dependencies need to be installed to be productive with the language (accomplished by integration with language-agnostic dependencies, such as Tree-sitter and a Language Server Protocol client).

As I’m developing the language, I want to be incrementally writing code in the language itself, whether that’s the standard library or other packages that I would intend to distribute independently from the core language in the future. Without basic niceties like syntax highlighting, auto-complete, auto-formatting, and integrated debugging, I won’t have a good feel for what working with the language will actually be like.

With the three stripes defined, I now have a roadmap for what my focus will look like as I’m making progress on the project. I can look forward to the completion of each stripe to demonstrate progress to myself and to release basic versions of the language to anyone who cares about it (no one at all, for now).

Implementation 🔗

As this isn’t meant to be a post about how to write code, there isn’t all that much to say about the implementation phase. We have an idea of the components that we need to implement and how those components relate to each other, so this process is about translating those ideas into code that is simple, efficient, and will remain easy to change as we continue to work within the system. How we approach each of these implementation decisions is a process of its own; though we could in theory apply striped development to each individual component within the design, I’ve found this to be more overhead than it’s worth in all but the most complex cases.

I can provide one very specific example of this type of decision: the introduction of source locations into the lexer. Without this concept, creating user-friendly error messages, even with such a tiny language, was already becoming cumbersome and error-prone. By implementing source locations, which automatically tag each lexed token with metadata about its context within the original source file, compile-time error messages now essentially write themselves. I’m sure this source location concept is going to have to be greatly improved as the language continues to evolve, but for the time being it’s a great tool that will make development of the actual language MVP much less painful.

If you’re interested in more depth on Jackal’s first stripe (and a more in-depth explanation of my goals for the language in general), you can take a look at the introductory summary for the language. There are compilation units for most of the components presented in the initial design:

It’s obviously not important to understand each of these in any depth, but it may be interesting to look at the public interfaces for each component and how they interact with one another. The implementation is quite simple right now, but I plan on keeping the repository up to date with more detailed information on how designs and implementations were required to change with each subsequent stripe, showcasing how we can achieve a robust and stable design through iterative thought and experimentation.

You may have noticed that the list of compilation units is missing an implementation for the semantic analysis (type-checking) component in the initial design. The language I used to construct the basic compiler infrastructure was untyped (all values were numbers), meaning that there wasn’t a realistic way to understand if the decisions being made within an semantic analyzer were correct or useful. As usual with striped development, embracing the iterative nature of the process means that it’s okay to miss a subset of the overall design on the first pass so long as we either update the design or implement the component in a subsequent phase. Striped development isn’t meant to be restrictive or prescriptive, it’s meant to give us context for our work and a plan that we can follow to accomplish our goals.

Conclusion 🔗

Striped development is a simple way to iterate on complex software projects. It can be used to design new systems from scratch, improve existing systems, or even act as a general development methodology for a team. It embraces the uncertainty inherent in system design and implementation. It provides a basic structure to help us constrain the difficult process of designing and implementing system-wide changes.

Give it a try sometime. I’d love to know what you think!